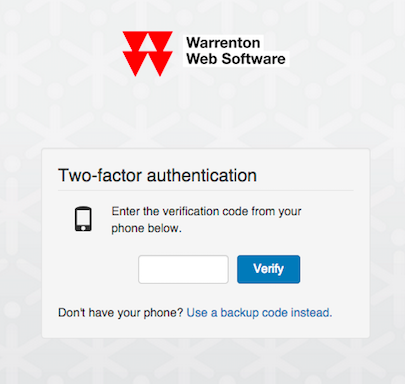

Different people have different security needs, but everybody agrees that having more security options is a good thing. Two-factor authentication (2FA), also called two-step verification, is one such option that is becoming more prevalent these days. Its purpose is simple: add an extra layer of security to the login process of your application (in our case, cloud.ca’s web console).

The Canadian Cloud According to cloud.ca

Cloud computing’s roots lie in the evolution of on-demand computing and computer networks. It has benefitted from important developments in virtualization, resource allocation and shared architectures. Now there is a true Canadian (Infrastructure as a Service) IaaS cloud.

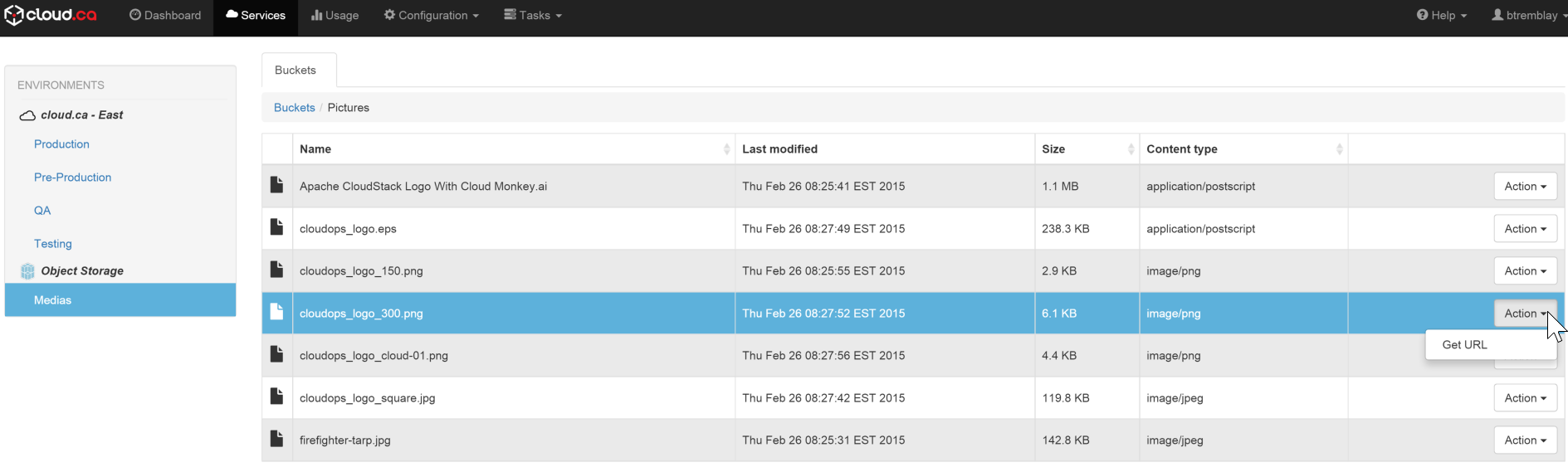

cloud.ca Object Storage; An Efficient and User-friendly Web Interface

A well designed object storage platform provides developers with an efficient way to access, store, protect and distribute their digital content independently.

The Three Stages of Cloud

The cloud is a powerful tool for business. Many company leaders are still debating whether or not to even use the cloud, without envisioning how the cloud can shape their long term strategy. This article aims to help resolve this debate by identifying the different stages of the cloud and the objectives that are attainable with each one.

New Architectures in a Cloudy World

Cloud computing is a victim of its own success. For one thing, cloud advocates have promised so much—worry-free, turnkey IT that just works— that the reality is bound to disappoint. Worse, clouds seem immune to tough economic times, so nearly every technology company is wrapping itself in a cloud mantle, and every dynamic website is claiming it’s a cloud. We don’t want to get bogged down in definitions, but any discussion of clouds requires a clear understanding of three things:

The Performance of Clouds

Cloud computing is a significant shift in the way companies build and run IT resources. It promises pay-‐as-‐you-‐go economics and elastic capacity. Every major change in IT forces IT professionals to “rebalance” their application strategy—just look at client-‐server computing, the web, or mobile devices. Today, cloud computing is prompting a similar reconsidering of IT strategy. But it’s still early days for clouds. Many enterprises are skeptical of on-‐ demand computing, because it forces them to relinquish control over the underlying networks and architectures on which their applications run. In late 2009, performance monitoring firm Webmetrics approached us to write a study on cloud performance. We decided to assess several cloud platforms, across several dimensions, using Webmetrics’ testing services to collect performance data. Over the course of several months, we created test agents for five leading cloud providers that would measure network, CPU, and I/O constraints. We also analyzed five companies’ sites running on each of the five clouds. As you might imagine, this resulted in a considerable amount of data, which we then processed and browsed for informative patterns that would help us understand the performance and capacity of these platforms. This report is the result of that effort. Testing across several platforms is by its very nature imprecise. Different clouds require different programming techniques, so no two test agents were alike. Some clouds use large-‐scale data storage that’s optimized for quick retrieval; others rely on traditional databases. As a result, the data in this report should serve only as a guideline for further testing: your mileage will vary greatly.

The Road to SaaS

Since the dawn of computing, there has always been a tension between centralized computing and computing at the edge. Mainframes were centrally managed, but as processing became cheaper; they gave way to minicomputers and servers. One reason for this was the high cost of bandwidth—as Microsoft’s Jim Gray once remarked, “compared to the cost of moving bits around, everything else is free.” So companies ran those servers near end users. This proximity came at a cost, however. The companies bought packaged software, which they tailored to their own needs and ran themselves. That caused fragmentation, so software vendors had to support a wide range of versions and deployments at the same time, reducing their ability to innovate. To address this, in the late nineties a number of Application Service Providers emerged. Their offering was reminiscent of the managed IT services that IBM, EDS, CGI and others had offered in the past, but it included the operation—and sometimes ownership—of the server and application stack. They ran software someone else made, and tried to streamline operations. Unfortunately, there was still a tremendous variety in client software. These ASPs had to contend with the twin horsemen of client sprawl and a stalled dot-com market, and many of them failed. But they weren’t wrong—just early. Meanwhile, a new generation of software companies built with only the web in mind. Salesforce.com, Taleo, Netsuite and others drew a different dividing line between themselves and their customers, choosing to own the entire software stack rather than license it from others. Borrowing a page from Henry Ford, customers could have any version of the software they wanted—as long as it was the current one, delivered by them, accessed through a web browser. And so the Software-as-a-Service market was born.